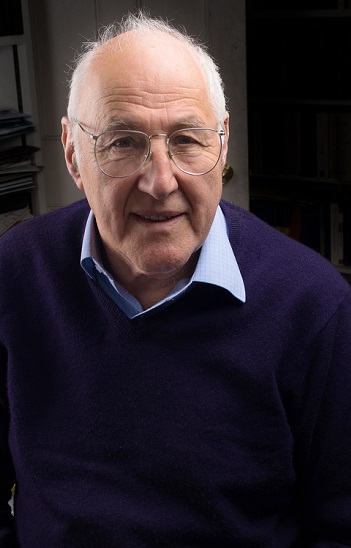

Celebrating 40 Years of CCLS: Professor Sir Roy Goode CBE QC

In 2020 we celebrated CCLS's 40th Anniversary. Sir Roy Goode, CCLS founder, talks about the challenges and triumphs along the way.

CCLS has been celebrating its 40th birthday in 2020. What were the challenges you faced when establishing the Centre in 1980?

CCLS has been celebrating its 40th birthday in 2020. What were the challenges you faced when establishing the Centre in 1980?

First, it was necessary to secure the support of the Faculty, which was concerned that the Centre might divert resources. They agreed when I explained that the intention was to make CCLS self-financing and make a significant contribution to teaching on the undergraduate programme. Second, the country was on the verge of a deep economic recession. Some of my colleagues thought I was mad to start then. But my view was that if we could weather the storm then we would be well placed when the economy improved, as, indeed, proved to be the case. The initial problem was how to get the Centre on the map. I invited Lord Hailsham, then Lord Chancellor, to open the Centre, which he agreed to do, launching it on 20 June1980 - and we were off! But a huge amount of effort had to go into raising funds from the private sector for new professorships and other posts.

Having watched it grow and develop over the past 40 years, what, in your opinion, have been the major highlights?

There have been many things to celebrate over the past 40 years, due primarily to the imagination and drive of successive Directors and the enthusiasm of the staff, including the secretaries, who worked well beyond the call of duty, helping to organise conferences and coming in at weekends to arrange the documents. The Herchel Smith Chair of Intellectual Property Law, established in 1979 through the initiative of the Chartered Institute of Patent Agents and the generosity of Dr Herchel Smith (who later bequeathed £6.5 million for intellectual property law within the Centre), was brought under the umbrella of the Centre, and we secured private funding for chairs in banking law, international business taxation and information technology law as well as establishing a School of International Arbitration.

A distinguished law professor, Professor Clive Schmitthoff, became joint chairman of the Committee of Management when well into his eighties and, vigorous as ever, he proposed that we jointly teach a course on international trade law, organise an annual international trade law conference and edit the papers for publications (I taught the course with him, everything else he did on his own). His widow left the greater part of her estate to the Centre to establish the Clive M Schmitthoff Foundation devoted to teaching and research in international commercial law. A whole range of other extra-curricular activities developed, including a full conference programme of continuing education, a three -week international commercial law summer school, an annual weekend conference in Creaton with the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators and a series of publications, some of which we were bold enough to publish ourselves, including the Commercial Law Bulletin. The College, having initially viewed with some reserve what must have seemed a decidedly anarchic department, developed such confidence in us that it agreed to the establishment of a chair of comparative law with no external funding at all. We became viewed by successive Principals of the College as one of the jewels in the crown.

Our committee of management (later Advisory Council) was always chaired by a judge. Two were appointed to the Court of Appeal, while the remaining four ended up as Law Lords/Justices of the Supreme Court. The moral: those who aspire to the highest judicial office could do worse than spend a term as Chair of the Advisory Council! We are fortunate that following his elevation to the Supreme Court Lord Kitchin continues to guide us in that capacity.

When I left Queen Mary in 1989 CCLS was still small but flourishing. In subsequent years it has been transformed by my successors into the largest centre of its kind in Europe and one of the largest in the world. It has established no fewer than eleven research Institutes in a wide diversity of subjects, it has about 1,000 postgraduate law students - the greatest intake of the London law schools - who select from a range of 54 courses or engage in doctoral research, it has developed a substantial programme of interdisciplinary activity as well as continuing professional development programmes and it has a flourishing LLM programme in Paris as well as links with a wide range of institutions here and overseas. All this has been achieved by the imagination and drive of my successors as Director and the enthusiasm of the incredibly hard-working staff.

How do you think the commercial law landscape has changed since you first started the Centre?

In several ways. There has been a huge growth in cross-border transactions, so that commerce and finance are truly global. This means, among other things, that a chain of transactions may be governed by different laws attracting the need for advice from lawyers in a variety of jurisdictions and transnational commercial law has become increasingly important. The size of transactions has grown enormously. This growth has been accompanied by the steady replacement of paper with the development of electronic payment and transfer systems, securities intermediation and more recently distributed ledger technology and smart contracts, and with all this has come greatly increased regulation. The Centre, based in one of the world’s leading financial centres and working closely with practitioners and national, regional and international organisations, continues to attract major research grants and is now offering online courses in dispute resolution and media and communications law and is providing technical assistance for the establishment of a new intellectual property court in Ukraine and the training of the judges, following a major award by DFID and the FCO. And it has its own in-house periodical, The Transnational Commercial Law Review.

Do you think young lawyers today are facing more challenges or have it easier than in the past?

Legal practice is much more challenging for today’s young lawyers than it was when I entered the legal profession some 70 years ago. They have to know a great deal more law and live in a highly competitive environment in which it becomes ever harder to secure training contracts and pupillages and, as qualified lawyers, posts in law firms and tenancies in barristers’ chambers. For the most part the changes over the years have seen great improvements in the quality of the profession. What are to be regretted, however, are the excessive hours which law firms demand of our brightest and best, who are left with little time for a social life if they aspire to a partnership, and the ever-growing demand to increase profits, whereas in the old days if you earned enough to enjoy a reasonable standard of living you were content.

How would you like to see CCLS develop over the next 40 years?

I feel diffident about expressing a view on this, as so much depends on the vision of each Director. But I would welcome a greater involvement with European scholars and practitioners, more joint publications and an increased focus on the social and economic aspects of national and transnational commercial law. Above all, CCLS must constantly strive not only to maintain but to enhance the quality of its student intake.

We are working to engage our alumni and make them feel part of the CCLS community, so do you have a message you would like to give them?

We greatly value their continuing relationship with CCLS, and hope that when they are in London they will find time to pop in and tell us what they are doing. Particularly welcome also would be any financial support, large or small, that they feel able to give CCLS to enable their successors as students to enjoy the same educational and other benefits that were enjoyed by our alumni during their time with us.