Entire amphibian communities are being wiped out by emerging viruses

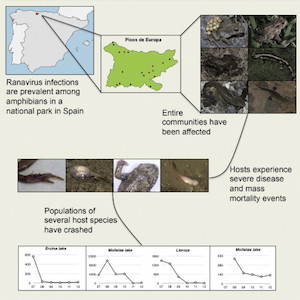

Scientists from QMUL, UCL, Zoological Society of London, and the National Museum of Natural Sciences (MNCN-CSIC) in Madrid, tracing the real-time impact of viruses in the wild have found that entire amphibian communities are being killed off by closely related viruses introduced to mountainous areas of northern Spain.

The viruses are causing severe disease and mass deaths in many amphibian species sampled, including frogs and salamanders. The common midwife toad, common toad and alpine newt were the worst affected, showing levels of population collapse which could ultimately prove catastrophic to amphibian communities and their ecosystems.

The results have wider significance as emerging diseases threaten all animal groups, including humans, where viruses have crossed the species barrier from other animals, for instance Ebola, which jumped from bats and other wild animals to humans. The paper, published today in Current Biology, reports a remarkable breadth of animals being infected including a snake which had been feeding on infected amphibians.

The viruses are part of the Ranavirus group which has previously been shown to only cause declines in the UK’s common frog – so this is the first time a member of the group (Common midwife toad virus or CMTV) has been found to affect entire host communities simultaneously.

From annual surveys across 15 locations in Picos de Europa National Park (PNPE) between 2005 and 2012, the team found animals from six amphibian species, of all ages, dead or dying from infection with CMTV. Through genetic analysis the team found all the viruses causing the infections stemmed from a single source with a near identical genome to the sample of CMTV found in the first infected animal in the Park.

In 2010, the team identified amphibian species over 200km away that were suffering with the same symptoms caused by Bosca’s newt virus (BNV) which is closely related to CMTV and a member of the Ranavirus group but is not found in PNPE. A third, more distantly related Ranavirus was found to be less virulent than CMTV, killing only the common midwife toad without causing mass-death or population decline.

First author, Dr Stephen Price of UCL’s Genetics Institute, who worked across QMUL, UCL and ZSL on the project, said:

“One of the main threats to biodiversity is the emergence of infectious diseases that can impact dramatically on entire communities. We’ve identified a striking example of two viruses that are repeatedly overcoming the species barrier with catastrophic consequences. This presents us with a great opportunity to understand more about the ecology and epidemiology of important multi-host pathogens.

Indications are that related viruses are beginning to emerge in other locations in Europe and it’s important to understand the origins and movement of these viruses to try to limit further amphibian declines.”

Other examples of pathogens with the rare capacity to simultaneously exploit a variety of new hosts to a similarly catastrophic degree include West Nile virus (infecting birds, humans, ticks, reptiles and amphibians) and white-nose syndrome in North American bats. The fungus causing white-nose syndrome has led to some six million bat deaths since 2006, with declining numbers of over 90% and the predicted extinction of at least one species of bat. This has left an estimated 1.1 million kg of uneaten insects which are causing crop damage, in turn affecting food supply and prices.

Prof Richard Nichols, Professor of Genetics at QMUL said:

"It is worrying that some viruses have jumped the species barrier and are causing population declines in several species, since our existing theory suggests only one or two species should be affected. We've just started a new project to follow up these results to investigate why some viruses are so very virulent in several species yet others, in the same ponds, are not. We hope that this knowledge will help us protect wildlife and even humans from future infections."

Research paper

You can read the full paper on the Current Biology website.

Read coverage of New viruses 'killing amphibians' in Spain on the BBC website.