QMUL academic unearths Britain’s first audiobook

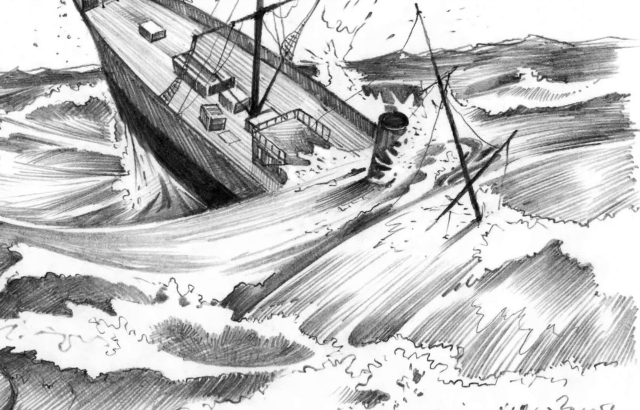

Matthew Rubery, Professor of Modern Literature at Queen Mary University of London, has rediscovered the first full-length audiobook ever made: Joseph Conrad’s 1902 novella Typhoon.

First recorded on a set of four long-playing shellac records, the audiobook was made in 1935 by the Royal National Institute of Blind People in London for World War One veterans who had lost their sight.

The sole surviving copy belongs to a Canadian vintage record collector, who realised the significance of the rare recording after reading about Rubery’s forthcoming book on the history of the audiobook. A blind veteran probably took the records with him to Canada after the war.

Rubery made the discovery while researching his new book, The Untold Story of the Talking Book, published this month by Harvard University Press. The book is a cultural history of recorded literature, which breaks with convention by treating audiobooks as a distinctly modern art form that has profoundly influenced the way we read.

The earliest example of recorded literature is Thomas Edison’s recitation of “Mary Had a Little Lamb” for his tinfoil phonograph in 1877. The Royal National Institute of Blind People started creating novel-length audiobooks, of which Conrad’s Typhoon was the first, for World War One soldiers who had returned from the front having lost their sight.

Other early audiobooks included Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd and The Gospel According to St. John. Both audiobooks were lost or destroyed.

Selecting books to record was a controversial process. Many blind readers complained that the books selected for recording were chosen because they were considered ‘beneficial’, rather than popular. There were also protests against censorship of “obscene” books containing sex, violence, and profanity (including classics like Muriel Spark’s The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie). Pressure from blind readers successfully led to the talking book library’s current policy opposing censorship in any form and allowing blind people to decide for themselves what to read.

Matthew Rubery said: “This is a tremendous find for anyone interested in literature, sound recording, or the cultural heritage of blind and partially sighted people. After years spent searching for the Conrad records in the US and UK, I’d all but given up hope of ever finding them.”

Mark McCree, Senior Manager: Library and Heritage Services, Royal National Institute of Blind People said: “RNIB Talking Books has such a rich heritage, it is wonderful that such an early piece of that history has been discovered. Last year was our 80th anniversary, and to find one of the 'original' collection recordings after all these years is reason to celebrate.”

Related items

28 July 2025

23 July 2025

17 July 2025

For media information, contact: