Cassini sees giant snowballs form in Saturn ring

New pictures from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft show giant 20 kilometre (12 mile)-wide snowballs forming in Saturn's fifth ring (the F ring).

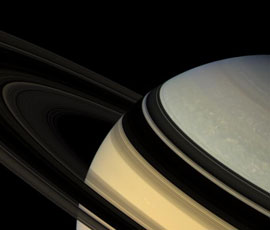

The planet Saturn and its rings

The stunning images capture the ring's icy particles clumping into giant snowballs as the moon Prometheus swings by the planet. Scientists speculate the process is similar to how the planets may have formed from dust orbiting around the Sun.

"Astronomers have never seen objects actually form in space before," said Professor Carl Murray, a Cassini imaging team member from Queen Mary, University of London. "We now have direct evidence of that process and the rowdy dance between the moons and bits of space debris."

In its orbit around Saturn for the last six years, Cassini has kept a close eye on the objects spinning around in the giant gas-planet's distinctive rings. Scientists say this is the only nearby natural laboratory where they can see the processes that must have occurred early in our solar system's life, as the planets and moons formed.

Murray discussed the findings today at the Committee on Space Research meeting in Bremen, Germany, and they are published online by the journal Astrophysical Journal Letters. A new animation based on imaging data shows how one of the moons interacts with the F ring and creates dense, sticky areas of ring material.

The Effect of Prometheus on Saturn's F Ring - read full caption (Image Credit: NASA/JPL/SSI)

The new data shows how the gravitational pull of Prometheus, the larger of the F ring's two 'shepherding' moons, sloshes ring particles around, creating waves that trigger the formation of giant snowball objects. It cruises around Saturn at a speed slightly greater than that of the much smaller F ring particles, but in an orbit that is just offset. As a result of its faster motion, Prometheus laps the F ring particles and stirs up particles in the same segment once in about every 68 days.

"Some of these objects will get ripped apart the next time Prometheus whips around," Professor Murray said. "But some escape. Every time they survive an encounter, they can grow and become more and more stable eventually becoming dense enough to have what we call 'self-gravity'. That means they can attract more particles to themselves and, er, snowball as more ring particles join them."

"This new analysis fills in some blanks in our solar system’s history, giving us clues about how it transformed from floating bits of dust to dense bodies," said Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. "The F ring peels back some of the mystery and continues to surprise us."

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. JPL, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington DC. The Cassini orbiter and its two onboard cameras were designed, developed and assembled at JPL. The imaging operations centre is based at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado. UK participation in the mission is currently funded by the Science and Technology Facilities Council. (STFC).

Related items

For media information, contact: