Are referendums the future of British democracy?

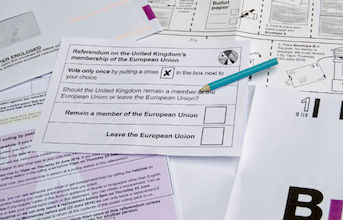

The 2016 Brexit referendum is having a profound impact on how the UK is governed yet for other countries referendums are a regular aspect of the political process. Queen Mary’s Mile End Institute hosted a panel discussion on 25 February to explore this topic.

The fallout from the Brexit referendum held in June 2016 has been profound. It shattered party loyalties and pitted the so-called ‘will of the people’ against their elected representatives.

Direct democracy has posed new questions about the running of campaigns, the role of the media and the working of Britain’s parliamentary institutions. In other democracies, such as Denmark and Ireland, referendums are not uncommon.

Chaired by Professor Tim Bale from Queen Mary’s School of Politics and International Relations, the panel discussion explored whether referendums can play a larger role in British politics and if so, what lessons can be learned from other countries?

The UK’s constitutional conundrum

Dr Robert Saunders from Queen Mary’s School of History presented a historical insight into referendums in the UK. He highlighted the fact much of the controversies surrounded the 2016 vote was as a result of there being no set rules on why referendums are needed in the UK.

“If referendums are going to be used more in British politics then thought needs to go into how the questions is framed, so we know what the instruction means,” he said.

Professor Meg Russell from University College London discussed the referendum in the context of constitutional reform, citing the lack of a written constitution in the UK as particularly problematic: “Nowhere else in the world can you change a constitution with a one-off vote.

“The UK has no written constitution but all previous referendums in the UK, whether on devolution, Scottish independence or Brexit, have all been on constitional issues. Referendums can help strengthen systems but when the system is divided, they can also weaken it,” she added.

Brexit led to new social identities – and divisions

Professor Sarah Bolt from the London School of Economics provided an analysis on the divisions that Brexit created. She argues that the referendum led to the emergence of new social identities and polarisation.

“Divisions in society were already there but the referendum exposed them. The referendum itself was polarising in that it was a sensitive subject, there was a binary choice and the result was a radical shift from the status quo,” she said.

“The UK government approach and the fact that there was no cross-party consensus also did not help to heal divisions brought about by the vote.”

A lesson from Ireland

Professor David Farrell from University College Dublin discussed the topic of referendums in Ireland. According to Professor Farrell, there have been 40 referendums since the ratification of the country’s constitution. In Ireland full details of draft legislation are published ahead of the vote taking place.

“The rules in Ireland mean that it is not just about the referendum question but what follows after the result is also taken into account.”

He cited the recent referendum on abortion as an example of how this works in practice, with people informed of what the next steps would be in the event of a vote for a constitutional amendment, before the vote took place.

“Compare this to Brexit where people were voting on something which was abstract since there was no legislation to review in advance of the vote,” he added.