Interview with Miranda Sachs about her book, An Age to Work: Working-Class Childhood in Third Republic Paris

Our member, Dr. Miranda Sachs (Texas State University, US), talks about her new book, An Age to Work: Working-Class Childhood in Third Republic Paris (Oxford University Press, 2023).

Q: What is this book about?

In the final decades of the nineteenth century, the French Third Republic attempted to carve out childhood as a distinct legal and social category. Previously, working-class girls and boys had labored and trained alongside adults. Concerned about future citizens, lawmakers expanded access to education, regulated child labor, and developed child welfare programs. They directed working-class youths to age-segregated spaces, such as juvenile prisons. Through their emphasis on age, these policies defined childhood as a universal stage of life. However, they also reproduced inequalities in the experience of childhood

In An Age to Work, I consider how the welfare state reinforced class- and gender-based divisions within childhood. I argue that agents of the welfare state, such as child labor inspectors and social workers, played a crucial role in standardizing the path from childhood to the workforce. By enforcing age-based rules, such as child labor laws, they attempted to protect working class children. But they also policed these children’s productivity and enforced gender-specific labor practices.

An Age to Work also enters the streets and apartments of working-class Paris to examine how the laboring classes envisioned and experienced childhood. Although working-class parents continued to see childhood as a more fluid category, they agreed with state actors that their offspring should grow up to be productive. They mobilized the welfare state to ensure this outcome. By interrogating these diverse perspectives, An Age to Work reveals that the same sort of welfare system that created social hierarchies in France’s colonies reinforced the class system at home.

Q: What made you write this book?

As an undergraduate, I had the privilege of working at the Cotsen Children’s Library at Princeton University. Cotsen has the largest collection of rare books and ephemera related to childhood in North America. My experience working at Cotsen piqued my interest in researching the history of childhood.

During my first research trip to Paris as a graduate student, I visited the police archives. In the late nineteenth century, each of Paris’ eighty police precincts kept a register of any incident that occurred in that district. When I began combing through registers, I discovered a number of records involving minors. Any time a young person was arrested, the police went to investigate their family situation. Almost always, the police recorded whether they thought the child in question was either lazy or productive. I was surprised by how present work was in these archives. I realized that the police perceived working-class children primarily in terms of their ability or capacity to work.

These sources made me start thinking about the differences in how people perceived childhood in Third Republic France. I found that even as the Third Republic enacted laws that protected working-class children, most legislators and reformers continued to see these young people as a specific group of the population.

An excerpt from Chapter 6:

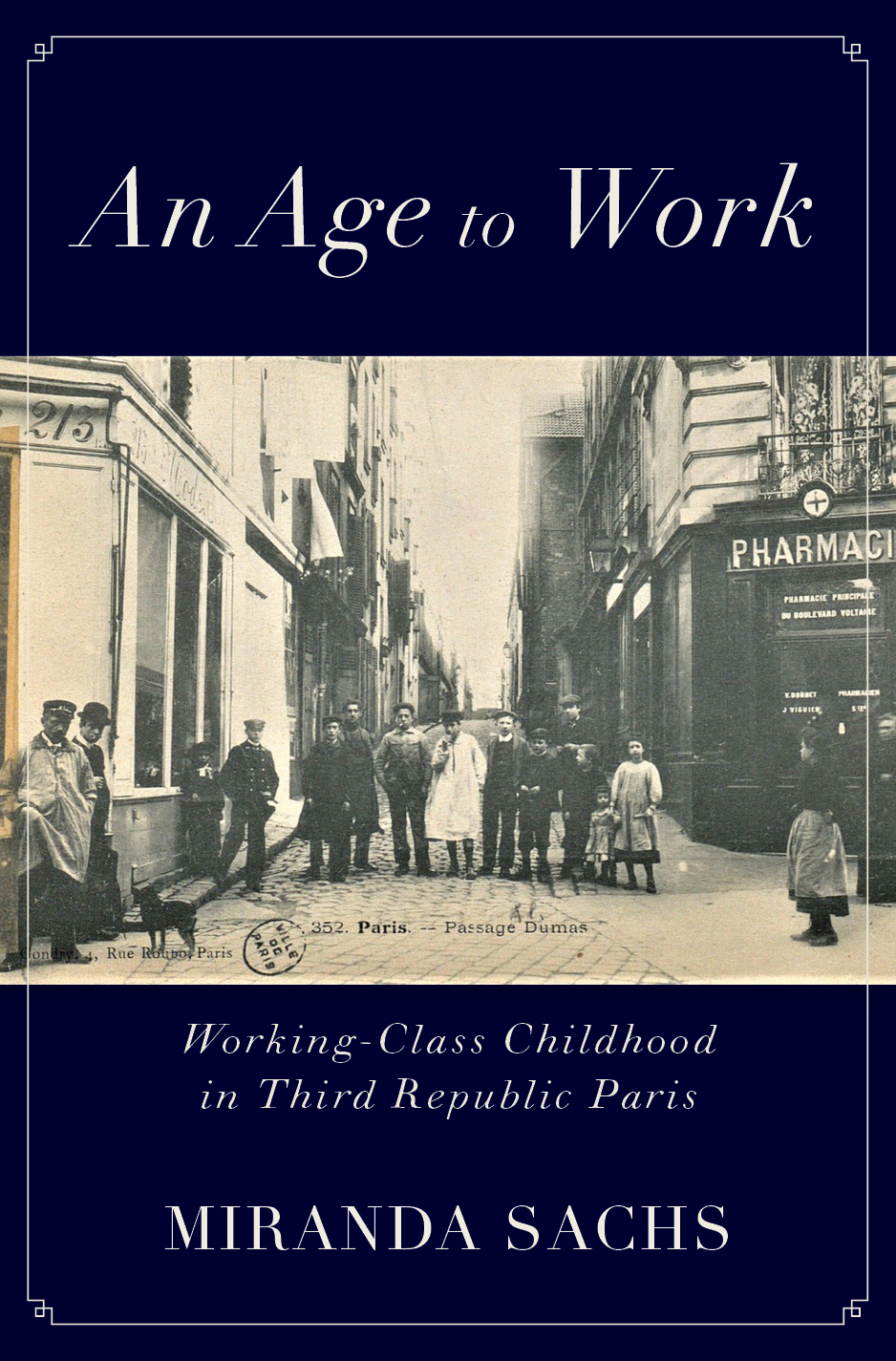

[The image referred to in the excerpt is the cover of the book]

A postcard of children and youths standing in the Passage Dumas illustrates how clothes marked a young person’s age, gender, and profession. The postcard is seemingly a naturalistic snapshot of the inhabitants of the working-class 11th arrondissement. At the same time, the image is carefully arranged, highlighting the differences in age and gender. Shot at a moment when early social scientists were seeking to categorize and make sense of populations, the postcard captures the organization within working-class neighborhoods.[i] The photographer listed at the bottom of the postcard had a shop a short walk from Passage Dumas, raising further questions about his relationship to the subjects.[ii] Did he collect a group of people and take them to a nearby street to pose? Or did he happen on this group as he was wandering through his neighborhood?

The variations in the subjects’ garments highlight the differences within the capacious working-class identity. Of the ten boys at the center of this photo, the boys closest to the girls are clearly the youngest. One has only knee-length pants, but already has heavy boots like Dabit. The next two, one just to the left and the other behind, are barely bigger, but wear the standard outfit for working-class men—long pants, vest, cap, collar, or tie. The five ranging from the center to the left are all workers and yet their appearance is quite varied. The central figure’s white smock suggests that he likely works in an artisanal trade, perhaps some kind of intricate metal work. The defiant boy with a cigarette sports a lighter-collared coat that buttons up to his neck, an outfit in which a number of teen-aged boys appear in postcards. He is perhaps an apprentice laborer. Boys in the food industry—either in shops or restaurants—wore aprons and occasionally ties, as with the two toward the left of the grouping. Finally, the boy on the left, slightly apart from the others stands out for the sharpness of his uniform. Probably, he delivers telegrams. This boy’s bright buttons and flat cap sets him apart him from the manual workers. Their edges are smoother and the colors they wear are more muted.

The grown men on the far left and the round-faced schoolboys stand in contrast to the working boys in the center of the photo. For the working boys, their clothes tie them to the adult world of work, but their smooth cheeks and small stature betray their youth. They seem as if they do not quite know what it means to be adult workers. The two boys in the center display almost opposite comportments. The boy with the cigarette stands tall with his hands in his pockets, acting the role of mature worker. At the same time, the boy next to him hunches over, his hand perhaps holding a sweet, in a much more child-like manner. As much as their clothes indicated that they had progressed beyond the classroom, these boys were still developing the stature and maturity required to participate fully in the workforce.

For girls too, their clothing signaled their age and profession. The girls at the right of the central group have not yet entered the formal workforce. Their garments are less fitted and only go to their knees. Even though the older of the two is likely the same age as the boys next to her and she is likely still in school, she is already taking charge of the younger girl. This smaller girl clings to her neighbor with one hand and holds what might be a toy in the other. In her apron and with her hair piled on her head, the woman on the far right has the dress of most working young women. Working women’s dress also had its own variations—clerks and shop girls were more likely to wear a white blouse that gave them a professional air—but this woman’s dark dress and apron is representative of the general appearance of female manual workers. Simonin even recounts that people in his neighborhood viewed young women with suspicion if they donned more fashionable dresses. It suggested that they had moved beyond simply selling goods to selling their own bodies.[iii] Clothes not only marked the stages of maturity of working-class girls, but whether they were following the socially acceptable path to maturity.

[i] See Susanna Barrows, Distorting Mirrors: Visions of the Crowd in Late Nineteenth-Century France (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1981).

[ii] “500 cartes postales,” Le photographe: Organe des syndicats et des photographes professionnels 4, no. 4 (January 26, 1913): 15.

[iii] Albert Simonin, Confessions d’un enfant de La Chapelle: Le Faubourg (Paris: Gallimard, 1977), 37