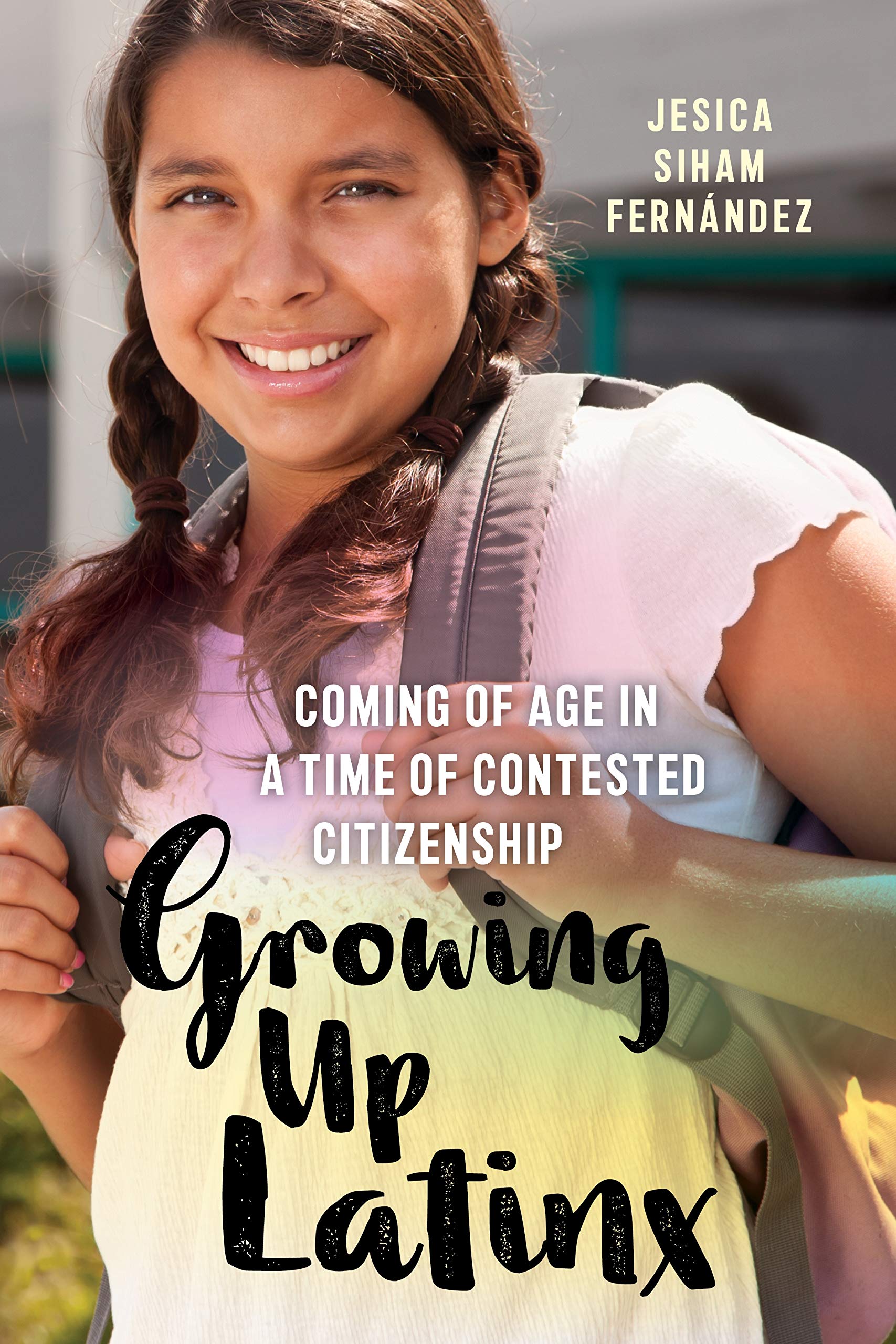

Interview with Jesica Siham Fernández about her book, Growing Up Latinx: Coming of Age in a Time of Contested Citizenship

Our member, Dr Jesica Siham Fernández (Santa Clara University, US), talks about her book, Growing Up Latinx: Coming of Age in a Time of Contested Citizenship (NYU Press, 2021).

Q: What is this book about?

Growing Up Latinx: Coming of Age in a Time of Contested Citizenship features the stories and voices of Latinx youth coming of age in the United States in immigrant and mixed-status families. Through Lagencyatinx youth reflections of their lived experiences in school, family, and community contexts, we are invited to reimagine citizenship and citizens in the United States. What does citizenship mean? Who is a citizen? How do Latinx youth growing up in the U.S. make meaning about citizenship and citizens? As Latinx youth embody and enact their sociopolitical citizenship, through their social identities, critical consciousness, socioemotional awareness, and political engagement, they reflect on these questions, and simultaneously trouble U.S.-based constructions of citizenship, legality, and rights.

Within the context of Change 4 Good (a participatory action afterschool program in a community in the California Central Coast), Latinx youth reflect upon their lived experiences as they challenge hegemonic discourses at the intersections of ageism and racist nativism. By creating a school-based community mural, Latinx youth engage their sociopolitical citizenship, as well as their agency to have recognized and understood their experiences, along with their hopes and dreams for their families and communities. Growing Up Latinx offers scholars, educators, and youth advocates an opportunity to re-center and support Latinx youth sociopolitical citizenship development—a pursuit that is possible when we listen and witness the power of youth in action.

Q: What made you write this book?

Scholarship examining the intersections of racism, nativism, and ageism that imbue Latinx youth lives is imperative in a US political context that continues to dehumanize and compromise the quality of life, well-being, and dignity of Latinx immigrant families and their children – this is the motivation that guided me to write this book. The book is anchored in the urgency to understand the contexts in which Latinx youth grow up in the United States to develop, engage, and make meaning of their positionalities as citizens, rights bearers, active participants, and in some cases advocates for their families.

By examining how Latinx youth defined and challenged constructions of citizenship, legality, and rights, as well as their poignant intersections, this book describes the social and political subjectivities of Latinx youth who are citizens in their own right—embodying and enacting agency in their school, family, and community contexts.

Growing Up Latinx, therefore, features the stories, reflections, and lived experiences of Latinx youth and their meaning-making about citizenship, legality, and rights in the United States, with the intention of expanding and challenging society’s views about who these young people are. The book invites readers interested in understanding the lives of Latinx youth to reconsider the meanings of citizenship that exclude young people.

In this way, Growing Up Latinx encourages us to engage in three actions. First, acknowledge and recognize that Latinx youth have agency. If provided with the resources, conditions, and opportunities to make their voices heard, they will speak up! And we must listen. Second, support and encourage the sociopolitical citizenship of Latinx youth by cultivating their agency via the development of their social identities, critical consciousness, socioemotional awareness, and political participation to create change in their communities. Third, challenge deficit views of Latinx youth that do not attend to the complexities of their lived experiences as young people who are embedded in social structures that view them as noncitizens, or future citizens at best.

Centering the voices of Latinx youth can contribute to the reimagining and transformation of US-based constructions of citizenship, legality, and rights. This effort to comprehend and center Latinx youth experiences is especially necessary for the democratic thriving of Latinx immigrant communities living in the US nation-state.

An excerpt from the book:

On an early afternoon in November, Lina and I sat on the bleachers of the multipurpose room of her elementary school watching students rehearse for the talent show performance. Lina is an outspoken, vibrant, and cheerful fourth-grader. However, on this day Lina appeared unusually quiet. I perceived that something was unsettling her, as she seemed deep in thought. I sat next to her, as she squatted hugging her hands over her knees in a cannonball-like shape. Slowly she adjusted her seat on the bleachers. Seated next to her, I leaned in to ask, “¿Estás bien?” (Are you okay?), to which she replied with a headshake, indicating no. I noticed her red eyes and sad expression as her face flooded with tears. I asked if she needed a hug, and as she leaned in she began to sob. I cried too. The reason for her pain was unknown to me, but I felt her pain. I held her as I asked again if she was okay, and she shared that she was afraid of the thought of having her father taken away. As she gasped for air and contained her tears, she began to explain how in recent weeks she had learned of the raids happening in the community, of deported family acquaintances, and of the fears and concerns her family was experiencing. I then understood the cause of her tears and pensiveness. Wanting to offer words of comfort but unable to find any, I listened to Lina share that her father “no tiene papeles” (has no papers, legal documentation), and “no es de aquí, como yo” (is not from here [United States], like me), and that she feared he’d be deported. She cried, “¡No quiero que se lo lleven!” (I don’t want him to be taken).

Lina, a second-generation Mexican American elementary school-aged student in a mixed-status family, was a vibrant, sociable, and outspoken youth. I met Lina during my time in the Change 4 Good youth participatory action research (YPAR) afterschool program located in a predominantly Latinx immigrant, low-income unincorporated community in the Central Coast of California. From the summer of 2009 through the summer of 2013, I helped coordinate Change 4 Good, and during this time I learned about Latinx youth lived experiences, like Lina’s, and how these informed their thoughts on citizenship, legality, and rights. Lina’s fears were heightened by the racist nativism and anti-immigrant sentiments that surrounded the political climate of an election year, hegemonic discourses that have become commonplace and amplified in the current context. Lina’s concerns, like those of many other Latinx youth in mixed-status families, reflected her experiences as a youth coming of age in the United States.

Lina’s story remains most vivid in my memory because it pained me to be reminded that there was very little that I could do to protect her family and prevent her from experiencing such anguish and possible loss. All I could do was comfort her, share with her my own immigration experiences, and offer a sense of hope that all would be well. Yet what I shared with Lina could not guarantee her father’s safety. I could not guarantee the rights, dignity, and respect that all Latinx and undocumented immigrants deserve. I also could not assure her a sense of belonging or a supportive environment that she and all Latinx youth are entitled to, regardless of their own or their parents’ immigrant status. To a degree, Lina’s fears of having her father “taken” paralleled some of the experiences my own family often endured because of our mixed status, fears that continue to be experienced by youth today.

Growing up in the United States, I, too, was seen as “not from here,” like Lina’s father. As trespassers, border crossers, and immigrants, Latinx hold differing positionalities and lived experiences in the United States. Yet regardless of the specificities of their immigrant status, Latinx are entangled in a citizenship regime characterized by the “institutionalized systems of formal and informal norms that define access to membership, as well as rights and duties associated with membership, within a polity.” The experiences and fears Lina expressed highlight aspects of her relationship to and meaning-making about the citizenship regime.

Like Lina, I, too, was attuned to the immigrant status of my family. Consequently, her concerns echoed my past insecurities and lack of belonging given my experiences in a Latinx mixed-status and transmigrant family. Latinx youth from immigrant and mixed-status families experience a unique, qualitatively different childhood than non-immigrant, non-Latinx youth in the United States. Socially constructed and legally informed meanings of citizenship, as well as legality and rights, inform Latinx youth understandings of their families as existing in a state of deportability, uncertainty, and fear. Latinx youth experience disparate social, cultural and political contexts. Yet some Latinx youth are provided with or able to gain access to resources and networks of support that facilitate their critical literacy to engage their agency in efforts to create social change. How Latinx youth understand, engage with, and trouble meanings of citizenship, legality, and rights at the intersections of the ageism and racist nativism they experience in their school, family, and community contexts is featured in Growing Up Latinx.