Researchers find long-term exposure to microbial pathogens results in childhood stunting

In a new paper published in Nature Microbiology, researchers from the Blizard Institute and colleagues from the Tropical Gastroenterology & Nutrition group in Zambia have found that constant exposure to microbial pathogens in children leads to stunted growth.

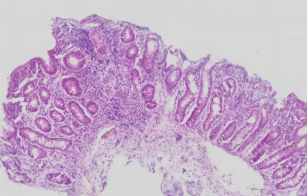

Small intestinal biopsy from child with refractory stunting

The research was based on a community-based longitudinal, observational study of stunting of 300 children in Lusaka, Zambia, from 2016 to 2019. Unlike interventional studies to address wasting and stunting, the authors assessed the intestinal pathology associated with stunting by using a combination of endoscopy and microscopy. They found that the constant exposure to microbial pathogens in children damages the lining of the gut, which affects food absorption and can in turn result in stunted growth.

They also found that young children with stunting that doesn’t respond to intervention have continuous, intense exposure to gut microbial pathogens and severe ongoing inflammation of the intestine, among other gut issues. The authors conclude that treatment should focus on healing the gut and minimising the child’s exposure to pathogens as they catch up in growth.

Corresponding author Professor Paul Kelly said: “We found very intense infection pressure with enteropathogens, but we also found evidence that the gut adapts to these pathogen burdens. Our data suggest that microbial translocation, through which gut bacteria get into the systemic circulation and trigger inflammatory cascades, can be controlled by adaptive responses which may lead to reduced nutrient absorption. In other words, stunting is the price you pay for staying alive."

There are 140 million children with stunting and 40 million children with wasting from malnourishment worldwide. Gut damage due to environmental factors is a major contributor to stunting in millions of children in Africa and South Asia. Previous research has shown that providing food and sanitary measures to undernourished children does not reliably restore growth, and that a proportion of children remain stunted.

Professor Paul Kelly added: “Malnutrition in children takes several forms, including stunting (failure of linear growth, reduced height) and wasting (often an abrupt loss of weight). It’s now clear that giving extra food only corrects about 10 per cent of stunting, and that refractoriness is in large part due to enteropathy, a disturbance of intestinal integrity and function.

“It would seem obvious that the appropriate treatment for malnutrition is food, and clearly without food no-one can recover from malnutrition. But often it’s not enough. Once children in disadvantaged populations become clinically malnourished, providing extra food is insufficient to guarantee recovery. We are going to have to be more subtle about unravelling this adaptive response than merely providing extra rations."

More information

- Research paper: Amadi, B., Zyambo, K., Chandwe, K. et al. ‘Adaptation of the small intestine to microbial enteropathogens in Zambian children with stunting’. Nat Microbiol (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-020-00849-w

- Find out more about the Centre for Immunobiology at the Blizard Institute

- Find out more about Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London