Researchers use Single-Cell RNA-Sequencing to Better Understand Gut Inflammation associated with Malnutrition

An international collaboration of researchers involving Queen Mary University of London has used single-cell RNA-sequencing to study environmental enteropathy (EE), thought to be a major contributor to malnutrition, to identify potential cellular and molecular targets for treatment and provide a roadmap for future EE intervention studies.

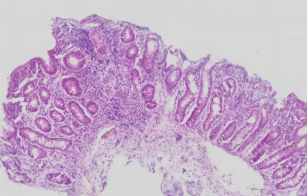

Small intestinal biopsy from child

Environmental enteropathy (EE), or gut inflammation due to environmental factors, is thought to be a major contributor to growth stunting, malnutrition, and reduced oral vaccine responses in millions of children and adults in low-resource settings.

The condition is often regarded as secondary to other issues such as frequent intestinal infections and poor access to sanitation infrastructure and clean water. While it is appreciated that gut inflammation can occur due to exposure to contaminated food or water, causing changes that make it difficult for children to absorb nutrients from food properly, exactly what those changes are at a cellular and molecular level remains poorly understood.

In a recent paper partly funded by Barts Charity and published in Science Translational Medicine, the researchers used single-cell RNA-sequencing to help uncover differences seen in the gut of individuals with EE. This is a technique that profiles the RNA levels of individual cells to better understand their characteristics and functions. They wanted to define the impact on the intestine of exposure to adverse environmental conditions in a disadvantaged community in Lusaka, Zambia.

They examined 33 small intestinal biopsies from 11 adults with EE in Lusaka, Zambia (eight HIV-negative and three HIV-positive), six adults without EE in Boston, USA, and two adults in Durban, South Africa. They also incorporated published data on three additional individuals from the Durban site.

Previous research that analysed EE biopsies histologically showed that in the small intestines of those with EE, the villi — structures that absorb nutrients from food — are shorter. It was also found that the gut’s barrier functions are responding in a pattern that resembles an attempt to keep harmful bacteria out, but which has the side effect of preventing nutrient absorption.

In the new study, the researchers found evidence that this may be due to gut intestinal epithelial cells differentiating into surface mucosal cells – mucus-secreting cells normally found in the stomach which help to protect against acid-associated damage. Furthermore, the team observed that these cells express antimicrobial genes including DUOX2, which had previously been described as a key marker of EE. Surface mucosal cells are normally not found in the small intestine.

One theory the researchers have is that mucosal cells may build up on the tips of the villi during wound-healing responses to infections from commonly occurring bacteria such as Helicobacter pylori.

By comparing EE samples with control cohorts, they also identified dysregulated WNT and MAPK cell signalling pathways and increased expression of proinflammatory genes in a subset of memory T cells.

Dr Paul Kelly, Professor of Tropical Gastroenterology at Queen Mary University of London and co-senior author of the study, said: “Comparing these cell profiles allowed us to identify perturbations in absorptive cell replication and differentiation alongside specific changes in tissue resident memory T cells. These changes align with known defects in the function of the intestine in individuals with EE.”

The researchers also studied the potential impact of HIV infection and antiretroviral treatment on the pathology of EE. They found that samples from HIV+ individuals had higher EE severity and that there were tell-tale signs of HIV infection expressed in the duodenal bulb, the part of the small intestine located closest to the stomach.

The work identifies correlates of EE that may be cellular and molecular targets for intervention in the future. “Our findings have identified multiple possible therapeutic and prophylactic approaches, as well as suggested possible mechanisms to explain the efficacy of prior interventions that showed benefit,” says Thomas Wallach, MD, physician-scientist and paediatric gastroenterologist at SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University and co-senior author.

He further noted “our observation of signals linked with immune tolerance may also shed light onto mechanisms underlying the hygiene hypothesis,” a possible explanation of the relative rarity of autoimmune and allergic diseases in low-middle income countries.

More information

- Research paper: Kummerlowe, C., Mwakamui, S., Hughes, T., Mulugeta, N., Mudenda, V., Besa, E., Zyambo, K., Shay, J., Fleming, I., Vukovic, M., Doran, B., Aicher, T., Wadsworth, M., Bramante, J., Uchida, A., Fardoos, R., Asowata, O., Herbert, N., Yilmaz, Ö., Kløverpris, H., Garber, J., Ordovas-Montañes, J., Gartner, Z., Wallach, T., Shalek, A. and Kelly, P., 2022. Single-cell profiling of environmental enteropathy reveals signatures of epithelial remodeling and immune activation. Science Translational Medicine, 14(660). DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abi8633